http://www.pbs.org/art21/watch-now/segment-mark-dion-in-ecology

Neukom Vivarium is a 2006 mixed media installation by American artist Mark Dion, located at Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle, Washington, United States. The work features a 60-foot (18 m) Western hemlockthat fell outside of Seattle in 1996, acting as a nurse log within an 80-foot (24 m) greenhouse. According to the Seattle Art Museum, which operates the park, the tree “inhabits an art system” consisting of bacteria, fungi, insects, lichen and plants. The installation supplies magnifying glasses to visitors wanting a closer inspection; they are provided field guides in the form of tiles.

“I think that one of the important things about this work is that it’s really not an intensely positive, back-to-nature kind of experience. In some ways, this project is an abomination. We’re taking a tree that is an ecosystem—a dead tree, but a living system—and we are re-contextualizing it and taking it to another site. We’re putting it in a sort of Sleeping Beauty coffin, a greenhouse we’re building around it. And we’re pumping it up with a life support system—an incredibly complex system of air, humidity, water, and soil enhancement—to keep it going. All those things are substituting what nature does, emphasizing how, once that’s gone, it’s incredibly difficult, expensive, and technological to approximate that system—to take this tree and to build the next generation of forests on it. So, this piece is in some way perverse. It shows that, despite all of our technology and money, when we destroy a natural system, it’s virtually impossible to get it back. In a sense, we’re building a failure.”[3]

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neukom_Vivarium

Mark Dion is a collector and a shopper. “I am constantly out there buying things, going to flea markets and yard sales and junk stores, and I like to surround myself with things that are inspirational.” Intrigued by natural history and museum procedures, Dion’s collections become part of his installations and public projects that address our ideas and assumptions about nature. “I’m not one of these artists who is spending a lot of time imagining a better ecological future. I’m more the kind of artist who is holding up a mirror to the present.” Viewers follow Dion on a journey during which he brings a “nurse log”—a fallen Hemlock tree which is home to a wide variety of flora and fauna—into the heart of Seattle. (From Art 21 PBS)

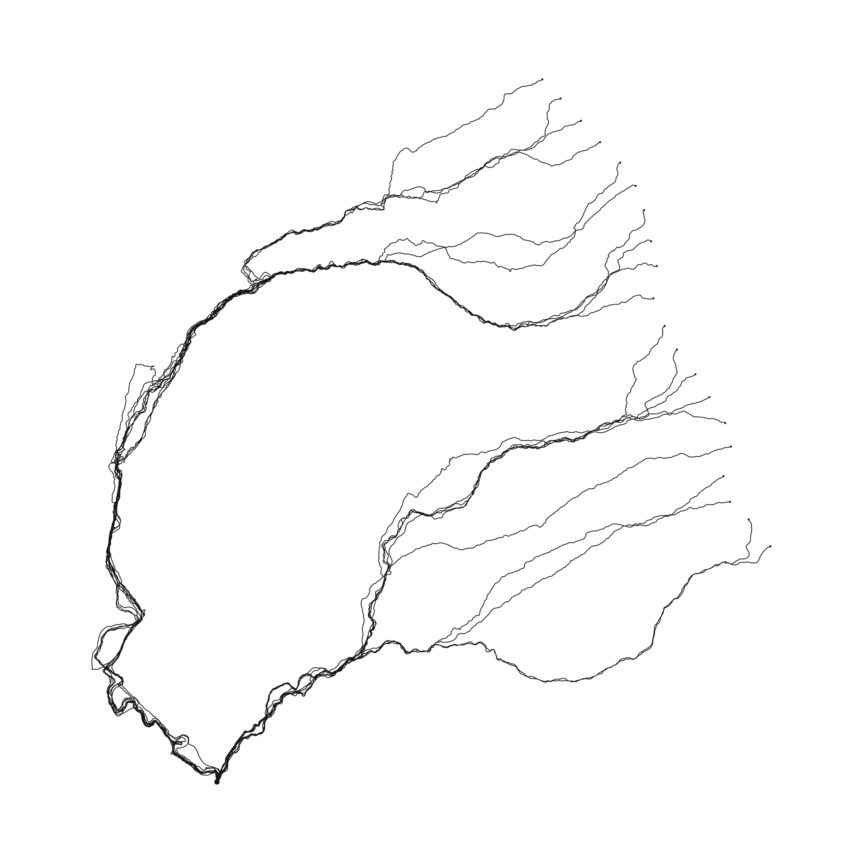

From Travels of William Bartram—Reconsidered, 2010.

“Investigating the visual representation of knowledge and the natural sciences, and concerned with the historical methods of representing and organizing the world, Mark Dion employs pseudo-scientific and museological conventions of investigation and display in order to subvert previously held ideas and practices.”

“Travels of William Bartram—Reconsidered is such a project and represents Dion’s extensive travels throughout the southern United States. In an effort to examine the history and culture of 18th century American naturalist, botanist and explorer William Bartram, Dion followed the approximate course of Bartram’s four-year expedition through eight southern colonies to take notes on the Native Americans and the indigenous flora and fauna. Using the original travel journals, drawings, and maps, Dion initiated his own, modern day, exploratory journey. Often traveling by horseback, canoe, and Jeep, Dion collected, scavenged and acquired numerous artifacts, specimens, and objects of material culture and mailed them back to Bartram’s Garden, the historic 18th century home of William Bartram, and his father John Bartram in Philadelphia.”

“Combining the physical beauty of history and science with the detritus of contemporary and past material culture, thousands of objects are beautifully and painstakingly categorized and arranged. Organized in various presentation cases and cabinets, according to form, material and subject, little distinction is given between high or low, or any inherent sense of value. Rather, Dion presents the display itself as a kind of democratizing filter, alluding to the wonder and magic of the every day. Found man-made elements include an extensive collection of toy plastic alligators, bottle caps from the decades between Bartram’s and Dion’s respective travels, cocktail umbrellas, pencils and buttons. Other shelves and drawers present organic specimens such as acorns, seashells, and pressed and dried vegetation harvested from the road and stacked high on a tall custom-built cabinet. As with all of Dion’s work, however, it is truly the artist’s selection and presentation that inspires the viewer; offering a fascinating investigation into the inherent contradictions between the artifact and the context in which it is displayed for our consumption.” From http://www.tanyabonakdargallery.com/exhibitions/mark-dion_1

Mark Dion: Library for Birds:

“22 live birds inhabit a circular chamber filled with books, photographs and artifacts

‘the library for the birds of new york’ also includes ephemera related to the capture of live animals — such as cages and traps — referencing the hunt and trade of exotic birds. as a longtime environmentalist, dion’s work recognizes the repercussions of human impulse to dominate nature.

other imagery acts as a metaphor for death, extinction, and the classification of birds as pests or vermin. these historical groupings are juxtaposed by a subtle suggestion — that birds possess knowledge outside of the human experience. the animals in flight are clearly uninterested in the objects at their disposal, underscoring the absurdity of the installation’s purpose — a manmade library for birds, which intends to educate them in subjects such as geography and the natural world, of which they inherently have full command. ”

mark dion builds a library for the birds of new york

an 11 foot high white oak symbolizes philosophical and scientific ideas

other imagery acts as a metaphor for death and extinction

all of the media included is related to birds, sourced from popular culture, art history, and film

From: https://www.designboom.com/art/mark-dion-library-for-the-birds-of-new-york-tanya-bonakdar-gallery-03-29-2016/

History of the Wunderkammer from the TATE Modern:

Where does the modern museum come from?

We know that earlier cultures such as the Babylonian (2200 BC – 538 BC), the Ancient Greek (1600 BC – 197 BC) and the Roman (396 BC – 410 AD) all had collections, which almost certainly had economic, religious, magical, historic, aesthetic or personal connotations for the owners. However, it wasn’t until the Renaissance (literally meaning rebirth) of art and literature in fourteenth-century that there consistently appeared collections which were preserved and interpreted – the modern definition of what a museum is.

These collections were created as a result of a growing desire among the peoples of Europe to place mankind accurately within the grand scheme of nature and the divine. This need developed during the fourteenth century and continued into the seventeenth century (the period of the Renaissance). These collections were generally known as cabinets, or curiosity cabinets, in England and France, and in the German speaking countries they were called kammer or kabinette. Greater precision was sometimes applied to the description of the collections in these cabinets, so there were kunstkammer (art cabinets), schatzkammer (treasure cabinets), rüstkammer (history cabinets), and finally wunderkammer (marvel or curiosity cabinets). Within the time period that these cabinets were created (the Renaissance) the terms wunderkammer or curiosity cabinet became the generic terms for them.

Wunderkammer or curiosity cabinets were collections of rare, valuable, historically important or unusual objects, which generally were compiled by a single person, normally a scholar or nobleman, for study and/or entertainment. The Renaissance wunderkammer, like the modern museum, were subject to preservation and interpretation. However, they differed from the modern museum in some fundamental aspects of purpose and meaning. Renaissance wunderkammer were private spaces, created and formed around a deeply held belief that all things were linked to one another through either visible or invisible similarities. People believed that by detecting those visible and invisible signs and by recognizing the similarities between objects, they would be brought to an understanding of how the world functioned, and what humanity’s place in it was.

The wunderkammer collections were displayed in multi-compartmented cabinets and vitrines, (which later in the Renaissance grew to be entire rooms), and were arranged so as to ‘inspire wonder and stimulate creative thought’ (Putnam p10). Exotic natural objects, art, treasures and diverse items of clothing or tools from distant lands and cultures were all sought for the wunderkammer. Particularly highly prized were unusual and rare items which crossed or blurred the lines between animal, vegetable and mineral. Examples of these were corals and fossils and above all else objects such as narwhal tusks which were thought to be the horns of unicorns and were considered to be magical.

As time passed and the wunderkammer evolved and grew in importance, the small private cabinets (which nearly all wunderkammer had begun as), were absorbed into larger ones. In turn these larger cabinets were bought by gentlemen, noblemen and finally royalty for their amusement and edification and merged into cabinets so large that they took over entire rooms. After a time, these noble and royal collections were institutionalized and turned into public museums.

From: http://www.tate.org.uk/learn/online-resources/mark-dion-tate-thames-dig/wunderkammen

You must be logged in to post a comment.