Button Project

I chose to make a few different politically and socially engaged buttons for this project as part of a larger exploration of text-based work and political work that my renewed participation in human rights movements has largely triggered.

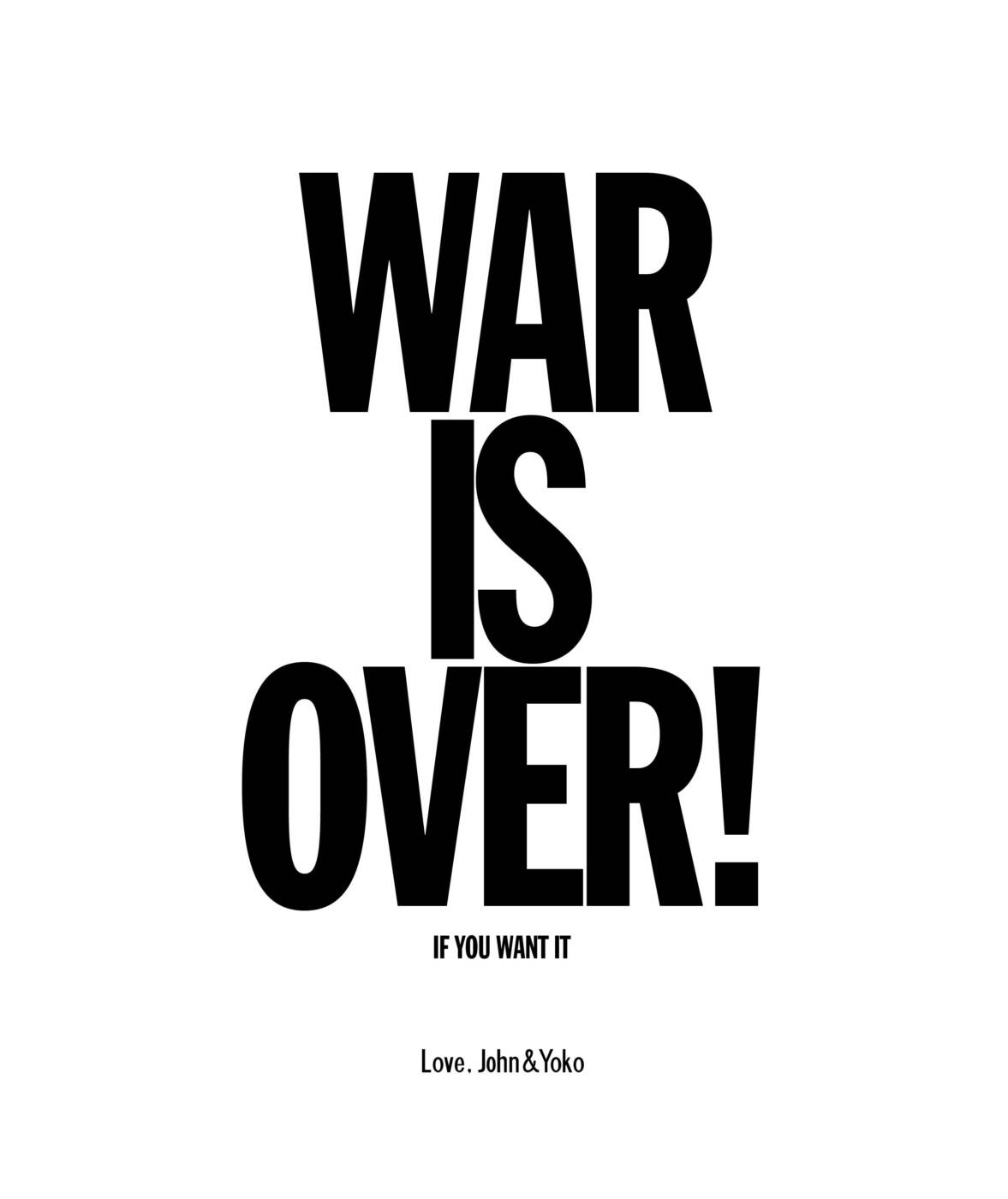

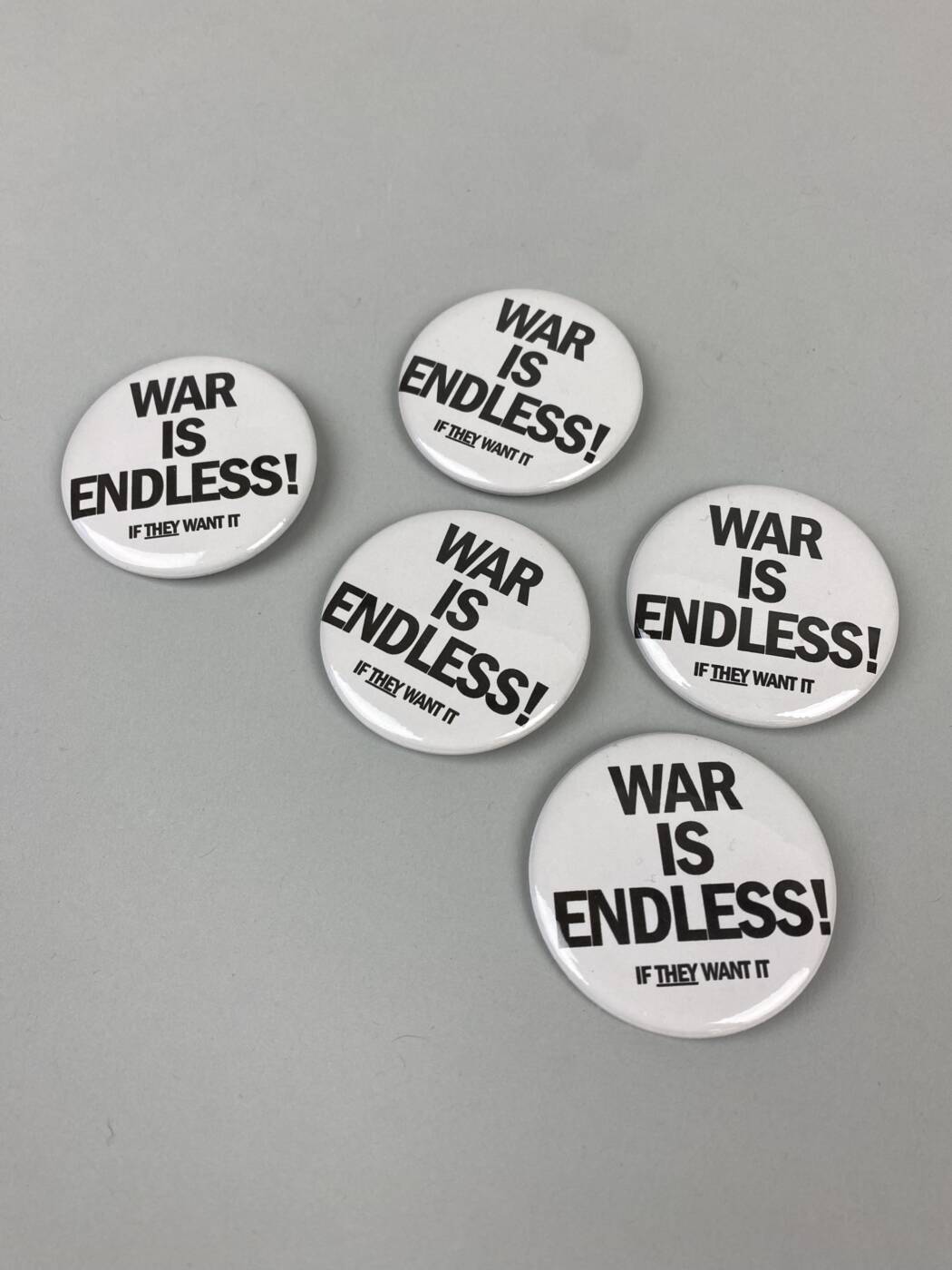

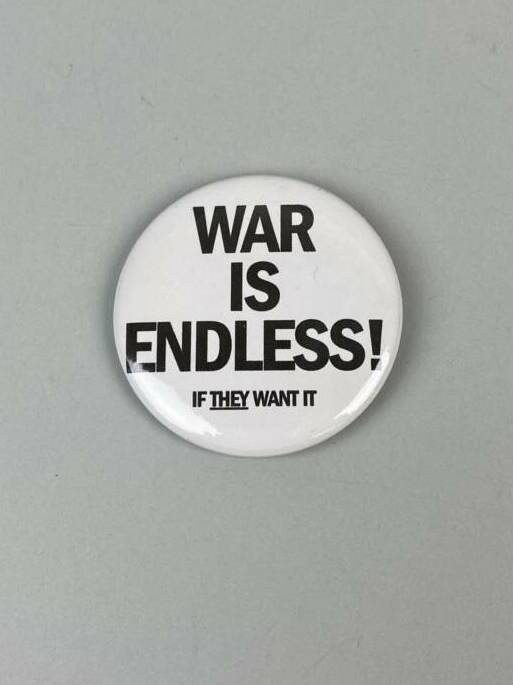

My first button is modeled after Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s “War is Over” poster. It appropriates their font and their message but turns it on its head to expose the realities of the war movement. Wars are fought by workers and innocents to financially and politically benefit the elite. I see it as a call to action for the people. Without revolution and a destabilization of the current system, war is endless, because the elite want it to be. War is not popular, yet it does not end.

This button provokes viewers and wearers to ask “Who wants war?” It provokes discussion of power and resistance to war and violence. It also questions the ability of political art like Ono and Lennon’s to provoke change. The original poster is over 50 years old, yet wars, genocides, and violent injustice prevail around the globe. How can we truly end the violence?

My second series expands on my last project where I made a tshirt that said “I don’t know what capitalism is.” I reused that phrase and added another: “I learned about capitalism on Instagram.”

Both phrases are pulled from personal experiences. A professor told me they didn’t think I knew what capitalism really was. That same professor warned me about falling into the stereotype of the “dumb woman who does all her research on instagram.” Both these statements made me feel small and they dismissed so much about me as an anti-capitalist artist. I took the opportunity to reclaim the phrases and wear them proudly. They become interactive, provocative statements that hold many meanings for many people.

I, like many activists have had to rely on instagram and other social media as a starting point from which I can seek out other sources. When much of mainstream news favours, for example, Israel in the genocide it is committing in Palestine, social media becomes a key factor for sharing knowledge and first-hand accounts. For me, learning about capitalism on Instagram is not a point of shame but rather of pride in the young people who labour endlessly to educate others and create a growing movement of solidarity with oppressed peoples worldwide.

Conceptual Portrait: I DON’T KNOW WHAT CAPITALISM IS.

I DON’T KNOW WHAT CAPITALISM IS. printed t-shirt, 2023.

I chose to work with text for this project. I had been looking at Jenny Holzer’s Truisms as well as referring back to previous works I’ve made surrounding text. The text-based work I enjoy the most is politically and socially active. My previous text works have looked at capitalist systems and government critique. I’ve included those works at the end of this section to help contextualize this new work in my wider practice.

I DON’T KNOW WHAT CAPITALISM IS pulls from a personal experience. I was told by a professor that they did not think I knew what capitalism was. As an anti-capitalist artist and student, I felt belittled. I wanted to subvert this phrase that was said to me and wear it proudly on my chest. “I don’t know what capitalism is” is a phrase that invites questioning, explanation, and thoughtfulness around the economic system we all live in in so-called Canada. It invites the viewer to ask themself: “Do I know what capitalism is?” “Does this person wearing this shirt need me to explain what capitalism is?” “Can I explain what capitalism is?”

I am also interested in the inherent performance of wearing such a statement on my chest. What does it mean to walk around in the grocery store wearing this? What about the dollar store? Or a public park? Or even a forest?

I wore my shirt for a full day of errands, chores, and even a leisurely hike.

This could be characterized as a performance or an experiment. In the future, I’d like to reperform my day in the t-shirt as it was pretty cold and I had difficulty boldly wearing the statement on my chest. The results of my wearing the shirt were not immediate, I did not notice anyone looking at me or questioning the words on my chest. If I had had the guts to wear the shirt more boldly and visibly, I think the results would have been different. However, I am quite shy by nature and had difficulty pushing myself on this particular day.

I am pleased with the photos I captured, especially the one of me scrubbing my bathtub. I think this photo in particular pushes this work into a feminist framework. It comments on the value of domestic labour in a capitalist system. I think having documentation of the shirt on a body really helps push the work into different concepts and meanings. I am excited to continue to pursue this type of text-based work beyond this class.

LAND LORD, silkscreen, 2022.

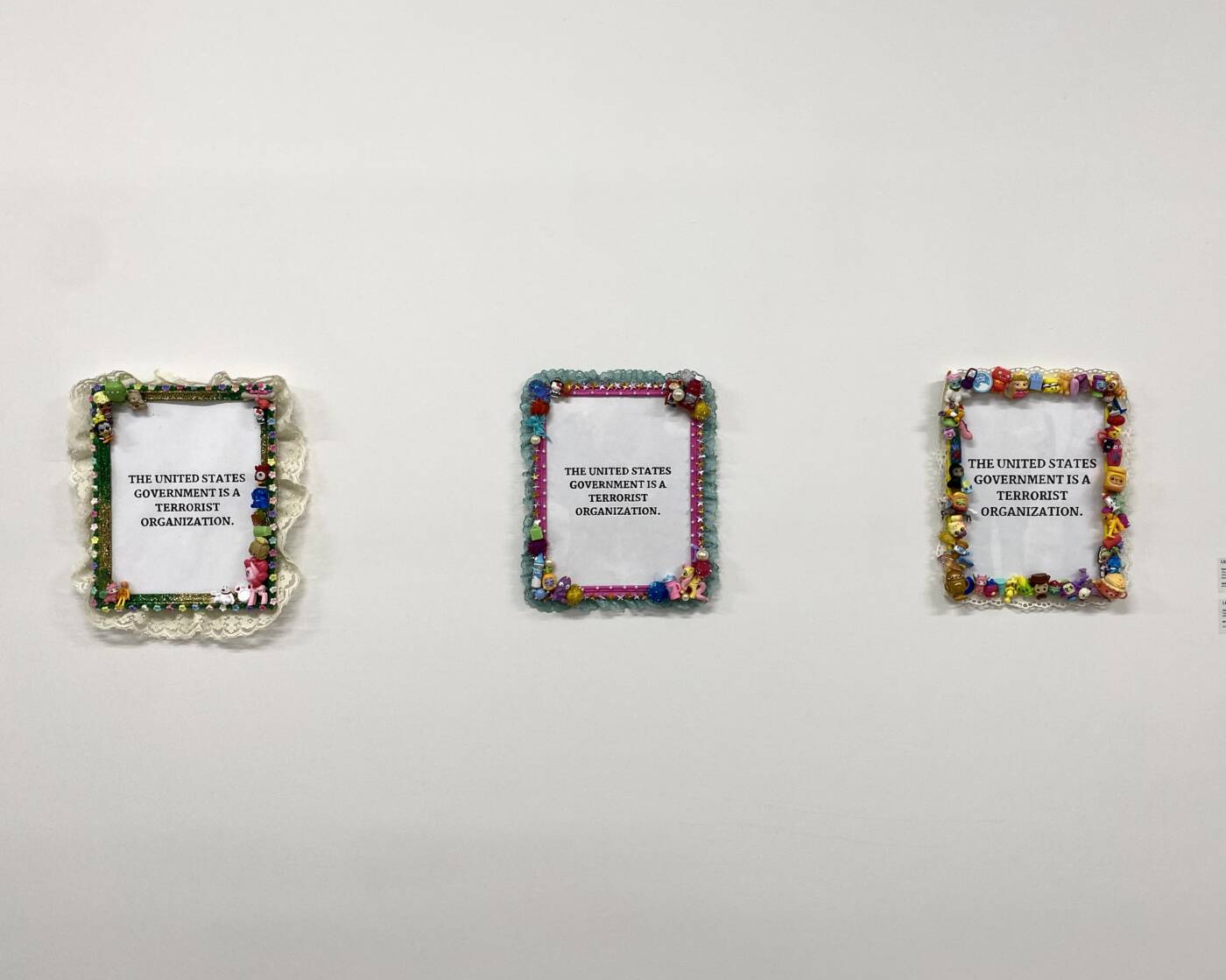

The United States Government is a Terrorist Organization (triptych), document frames, paper, ink, plastic, lace, toys. 2023

Audio Project

Women Love Being Cheated On

This work takes clips from a popular white, anti-feminist creator named Pearl Davis. Davis has made a platform for herself on many forms of social media. She is a strong anti-feminist who has even advocated for divorce to be banned and for women to lose the right to vote.

Today’s hyper-individualist society is rife with far-right wing politics that dismiss oppressed people in all forms. North American society is a breeding ground for hateful, misinformed rhetoric and ideology. Pearl’s evangelist, white supremacist ideology about feminism and women in general is a dangerous example of the kinds of thoughts individuals have. I chose Pearl because of her refusal to talk about race, disability and class in her discussions on feminism. This work creates a portrait of the type of disillusioned white woman who feels her livelihood, and womanhood is threatened by the intersectional feminism that seeks to include all genders, races, abilities, and classes.

Video Art

For this work, I chose to focus on hair as the subject. I take special care with my hair. I have been growing it for many years and will continue to do so for many more years. Each night I brush and braid my hair before I get into bed.

I am a queer, femme person in a straight-presenting relationship. My partner is a cisgender man and I often think about my queer identity in the relationship. I am his girlfriend, but am I really a girl? My hair ties me to my feminine identity, but I often feel like my hair is less indicative of my gender and more representative of a routine of care I do for myself.

I used this video assignment to explore this haircare routine, which I often do as I get ready for bed with my partner. I want this work to make connections between gender and hair, sexuality and hair, and emphasize my gender identity in relation to the cisgender man I share my life with.

- One shot “Brushing Sam’s Hair with Care”

2. Loop “Endless Care”

3. Sequence “Braiding Together”

Pipilotti Rist

- Post an image from one of Rist’s videos that you are most interested in. Summarize the action of the video. Who is performing, and how? Describe the images – including framing, colours, and movement. How did she shoot and edit the video? Describe the sound and how it interacts/enhances/competes with the images. How is it installed in a gallery – in terms of projection/scale/presentation in a context of other things? How does the work strike you?

From Rist’s early work to now, installation has been of utmost importance to the meaning and experience of the work. I encountered Rist’s Selfless in a Bath of Lava early in my undergraduate degree and have often thought about that tiny screen and its ability to be walked over and completely ignored (intentionally or not).

The tiny screen (only the size of a matchbox according to Randy Kennedy for New York Times) is installed in the floorboards of a space. It shows Rist herself, nude, reaching up so as to not be engulfed in the ‘bath of lava’ beneath her. Below is an image of this work as it is typically installed. The floorboards are chipped away irregularly, and the screen is set below the surface of the floor.

As mentioned, Rist is performing. She is naked, reaching up and pleading for help. She says “Help me” in various languages as well as “I am a worm and you are a flower. You would have done everything better!”. The video is shot from above, just as the viewer is intended to be above Rist upon installation. The angle, coupled with her nudity and self-degrading comments reflect vulnerability. It is difficult to ignore the feminist undertones of this work, her position beneath the floor can be understood as a critique of patriarchal society where women are perceived as the lesser gender, positioned below men in the social hierarchy.

Her movement and speech is almost childlike, again reinforcing feminist ideas in which women and children are often placed in the same category of weakness, helplessness and vulnerability. The bright, saturated colours on the screen can also evoke childhood and playfulness; despite nudity and the impending violent death in a bath of lava.

The audio is quiet, the viewer must crouch down and get close to hear the tiny voice coming from the floorboards. Scale and audio work together to make sure that the viewing of the work is intentional and that those looking around the gallery absentmindedly will miss it.

2. Rist has had a long career in video art making – how do you relate it to the kinds of video that you might see all the time on Tik Tok or You Tube, in our time? Reflect on her performances and also – on her ideas (particularly about women’s bodies, and sexuality, exposure, behaving strangely or subversively…) and how they play out from examples in her works.

To begin answering this prompt, I thought I would speak about the direct relationships I could draw between contemporary media and Pipilotti Rist’s work. During class, we viewed “Ever is Overall” in which Rist’s friend walks down a city street with a metal replica of a “Red Hot Poker” (a flower) and uses it to smash car windows. She looked gleeful as she trotted down the street in her dress. Similarly, on Beyonce’s 2016 album Lemonade, the song Hold Up’s music video shows Beyonce herself walking down a city street gleefully, using a baseball bat to smash car windows. Watching Rist’s film immediately evoked Beyonce’s music video, which was iconic and exciting at the time of release. I had never realised that this video appropriated Rist’s performance.

Ever is Overall inspired Hold Up, and Hold Up has inspired other reproductions in film, television and on social media. My favourite reproduction being from the Netflix original show Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt.

It is endlessly interesting how the art world infiltrates popular culture and how each new interpretation of the work reaches further from the original. We go from Pipilotti Rist’s video, which repackages female rage as beautiful, gleeful and ultimately ‘feminine’. Beyonce’s interpretations takes on a new meaning as she adds her song about being a victim of infidelity. Her position as a Black woman also transforms Rist’s rage to give it new meaning. Beyonce looks gleeful, like the performer in Rist’s video, however Beyonce’s video confronts the ‘angry Black woman’ stereotype instead of just general female rage. Then, the concept is flipped on its head again as a Black gay man performs it in Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. It becomes more comedic than conceptual, and begins to lose its roots in Rist’s work.

Rist’s work can also connect to more accessible and widespread forms of video media. TikTok is probably the largest short video platform in the western world. It sets a precedent for how videos are consumed, with most social media sites having introduced some short video feature in the last five years. Feminist artists working with video such as Pipilotti Rist set the stage for so-called amateur video-makers on TikTok to engage in their own commentary about body image, womanhood, female sexuality, self-surveillance and other feminist ideas.

In the last year or so, a trend emerged called “corecore” in which creators make compilations of a variety of videos to evoke a feeling of discomfort. A very common theme of these videos is womanhood, some explore female rage, which I think connects to themes of Rist’s work. Corecore videos showcase an aspect of womanhood, sometimes being misogyny experienced, sexual abuse, harassment and patriarchy. These videos are, in my opinion, contemporary video art, outside of the institution of the gallery or museum. I’ve linked a couple below.

3. Experiment: While still at school – put on your sweater/shirt INSIDE OUT. How does this change how you feel? Is it changing how others are treating you? If you can wear your sweater/shirt inside out all day – make a few notes about the results of this very small change in your presentation in public. Is this a performance? Why?

For me, wearing my shirt inside out posed more personal problems than issues wondering what people might think of me. I knew few people would notice my clothes, especially on the packed bus I took to school. When I walked through Branion Plaza I knew some people would notice, as there are typically students eating lunch and people-watching, I often sit and watch people. I was not super bothered by them, especially since it was my t-shirt that was inside out and I had put an open button down on top to keep me warm. So my irregular clothing was not fully visible. My biggest issue was that I was physically aware that my shirt felt wrong. It irritated me and the print on my shirt touched my bare skin. I had to fix my shirt during a break in my class, I could not take it anymore.

In terms of this being a performance, I am still not sure. I was certainly performing for myself since I seemed to be the only one to notice the way my clothes were being worn. But as far as engaging a viewer, I don’t think I was successful, nobody seemed to care to watch me. But a performance can be just for me, and maybe this was a performance only I engaged in.

My Kilometre

Background:

I have a hard time walking far distances. From the many buses that come to my stop, I always choose to take the 99 Mainline because it drops me off closest to my classes. When my partner (who loves to hike) plans walks for us together, he knows he has to keep my bodily limits in mind. Uneven ground makes my weak ankles sore, long distances begin to hurt my legs, toes and back. I am adjusting to this everyday pain that has become more of a problem in the last year. At only 22, I am fearful of how my current pain might progress in the future. Nonetheless I like to be outside. I like to move my body and I like to walk.

Process:

I walked from around 8:20 pm-8:30 pm in a relatively open space in the university’s Arboretum. I walked mostly on grass. My partner followed my path with my phone in his hand. He used the app “AllTrails” to map my exact route. I walked until I felt like I had walked a kilometre, but I had no way of knowing whether I had walked more or less than the 1000 metres usually prescribed in a kilometre.

I took an unconventional path. I chose an open space rather than a pre-existing trail for safety due to the low light conditions. I also chose an open space because I knew I did not want to walk in a straight line or along a path. I wanted to make my own path based on my own decisions and intuition. My route zig-zagged, looped back on itself and had sharp turns: all of these things stopped me from being able to measure physical distance travelled and forced me to rely on my body and how it felt.

What Happened?

I walked just over 600 metres at dusk. I stopped because I felt like I had walked a kilometre. My body was giving me signs that I had travelled some distance. I began to have some shooting pain in my right foot. So I stopped and asked my partner to show me my progress. That night, 600 metres was my kilometre.

How is this exactly a kilometre?

This is MY kilometre, based on my body’s limits on that evening. It is not a kilometre in terms of the metric system, rather it is a kilometre based on feeling and body.

I figure that I have many different kilometres. There was a sense of disorientation as dusk turned into darkness. I had no visual sense of how far I had travelled, only perceived time and bodily feeling. Perhaps in the daytime my kilometre would measure 1300 metres.

This experiment, done at night, forced me to rely less on vision and more on feeling to distinguish my kilometre.

Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present

Question 1

My first impressions of Marina Abramovic based on the documentary are mixed. I have been somewhat familiar with her work based on my studies in contemporary art history throughout my undergraduate degree. I have always found her compelling but was shocked to find that some of her work made me deeply uncomfortable. The main work, The Artist is Present made me emotional. There were tears forming in my eyes.

The aspect of The Artist is Present that struck me the most was the shift in vulnerability in the artist herself. 2 weeks before the opening at the MoMA, Abramovic was ill, and the film showed her clad completely in red, even eating red oranges. She said that red is a colour of strength, and she felt she needed all of the strength she could get in preparation for her retrospective. She had fallen ill just weeks before a 3 month long performance, after all.

What is especially interesting is that this red aura of strength followed her into the first two months of her performance. All day, for six days of the week, for two months, Abramovic sat unmoving in her red gown, which covered her from neck to wrist to ankle. She sat opposite her audience, separated by a table. She was protected by her strength in red and by the structure of the table in front of her.

The month of May, the final month of the exhibition, saw a shift in the performance. Abramovic began wearing white. She removed the table that protected her. She stripped herself of her strength and sat, truly vulnerable to the audience in front of her. It is admirable to watch her shift her performance. It became more emotionally heavy as these shifts occurred. The film showed more emotionality in both the audience and the performer after this shift took place.

I was not struck the same way by another work in the show, titled Luminosity, originally performed for 2 hours by Abramovic in 1997. It was reperformed by young artists for the retrospective at the MoMA. It is an uncomfortable piece for me, that is not to say that it isn’t a good piece of work. I am just made more uncomfortable by nudity than some. The nudity coupled with the pornographic position of the woman makes it hard for me to watch. The woman stands, largely unsupported on two small platforms. Her other source of support is a microphone shaped object pressed against her vagina. It looks torturous as she slowly moves her arms up and down. The female body will always be viewed under the male gaze, especially when nude. It is impossible to escape. I think that is where my discomfort ultimately comes from. In Luminosity, Abramovic unfortunately provides a vessel for the male gaze, and perhaps that is the point.

The work is still effective despite its implication of patriarchal male gaze. In its reperformances during her retrospective, Abramovic’s work took on new meanings based on the bodies performing. A Black woman taking on the role had a vastly different significance to Abramovic’s own white body. Women of colour being placed in the performance evoked themes of white supremacy, unpaid labour and slavery, bondage and freedom.

Question 2

Abramovic’s work shows performance art as a lifestyle and a lifelong kind of work. It looks at human relationships and humanity itself. It challenges the body and the mind equally and pushes the boundaries of the gallery and the world at large. Marina Abramovic is a highly dedicated performer who refuses to quit. I remember learning about her performance in which she burned a five point star while laying in the middle, and she passed out from lack of oxygen. Luckily an audience member noticed her lose consciousness and disrupted the performance. I remember my professor saying this disruption was somewhat unwelcome to Abramovic. She sought to push her body to its absolute limits.

In the documentary, those close to her assert that Abramovic is never not performing. She says that “performance is a state of mind”. Performance art uses the body as medium to explore some sort of relationship. Her work with Ulay explored the dynamic between man and woman. Her solo work challenged her physicality while building a strong bond-like relationship with audience members (especially in The Artist is Present).

Her performance is real, it is intense and it captivates viewers. She is never acting. Her performance becomes her life. Her intense discipline, rooted in her childhood in former Yugoslavia, benefits her craft as she is able to sustain long, exhausting performances. She is often thought of as the grandmother of performance art. She paved the way for many other artists. One aspiring performance artist is shown in the documentary. She walks up to Abramovic in The Artist is Present and disrobes. She is immediately removed by security. However, it could be argued that she was only following in Abramovic’s footsteps in breaking the status quo in the institutions of the art world.

Question 3

The institutions that control the artworld exist not only as cultural pillars of society. They also operate in the context of colonialism and capitalism. The roots of most major museums in North America and Europe are within stolen land, stolen objects, and stolen labour. The art world, when Abramovic joined it, would have been highly centred around white men and the physical objects they produce. Her work, along with the work of other early performance artists responded to the physicality and the permanence of the art world. It rejected the idea of making art to be bought and sold as commodity, and embraced ephemerality.

Her performances are not always available to watch in full anywhere. Some works exist only in those who made up the audience. Many exist only in photographs. These works reject commodification and they reject the traditional gallery/museum space. The documentary asserts that during her early career, and her time with Ulay, she was very poor. There was not a whole lot of art collectors able to buy her work, because it was not for sale. As her career grew, gallerists and curators grabbed ahold of her rising star and began coming up with ways to make money in a way that honoured the ephemerality of her work. Abramovic sold limited series of stills from her performances at over $2,000 a piece. Her work began to participate in the colonial capitalist art world. It had been commodified.

An artist has to make a living. It’s impossible to disengage completely from the art world to make critique about it. Marina Abramovic, however, became a superstar. She has clearly become very wealthy based on the scene in the documentary where she has a personal shopping experience with the creative director of Givenchy in which she considers purchasing an $8,000 jacket. This scene undermined a lot of her institutional critique for me. It feels as though she has shifted from disrupting the system of the art world to participating in it in a lot of ways. Though, much of her integrity remains as she continues to make performance art that is laborious and difficult. She still shifts the power of art and includes the audience wholeheartedly, though she does it in expensive clothing now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.