Experimental Films of Andy Warhol:

No survey of the second half of the twentieth century would be complete without mentioning Andy Warhol. More commonly known as the pop master of the silkscreen painting, Warhol was also the maker of over 400 films. From the early minimal works such as Sleep and Blow Job, to the later epic The Chelsea Girls, Warhol was a highly active disciple and proponent of the moving image, at least from the time he acquired his first film camera in 1963. Shot in 1964, and lasting a soporific five hours and twenty minutes, the film Sleep was one of his first experiments in film making and consists of Warhol’s lover at the time, John Giorno, doing nothing other than sleeping. Described by Warhol as an “anti-film”, he would later extend the same filming and cutting technique to eight hours for his subsequent film Empire, constantly solely of footage of the Empire State Building.

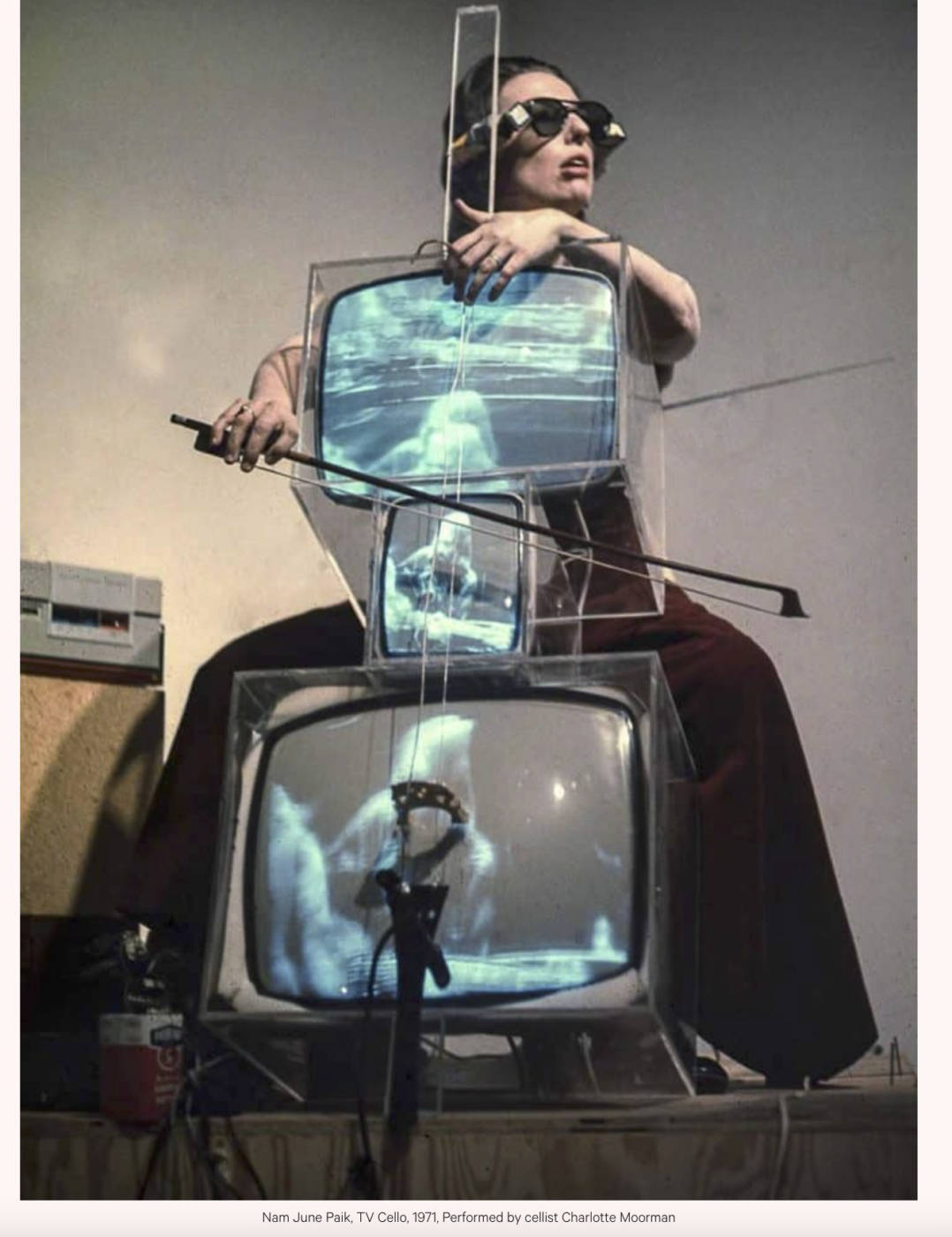

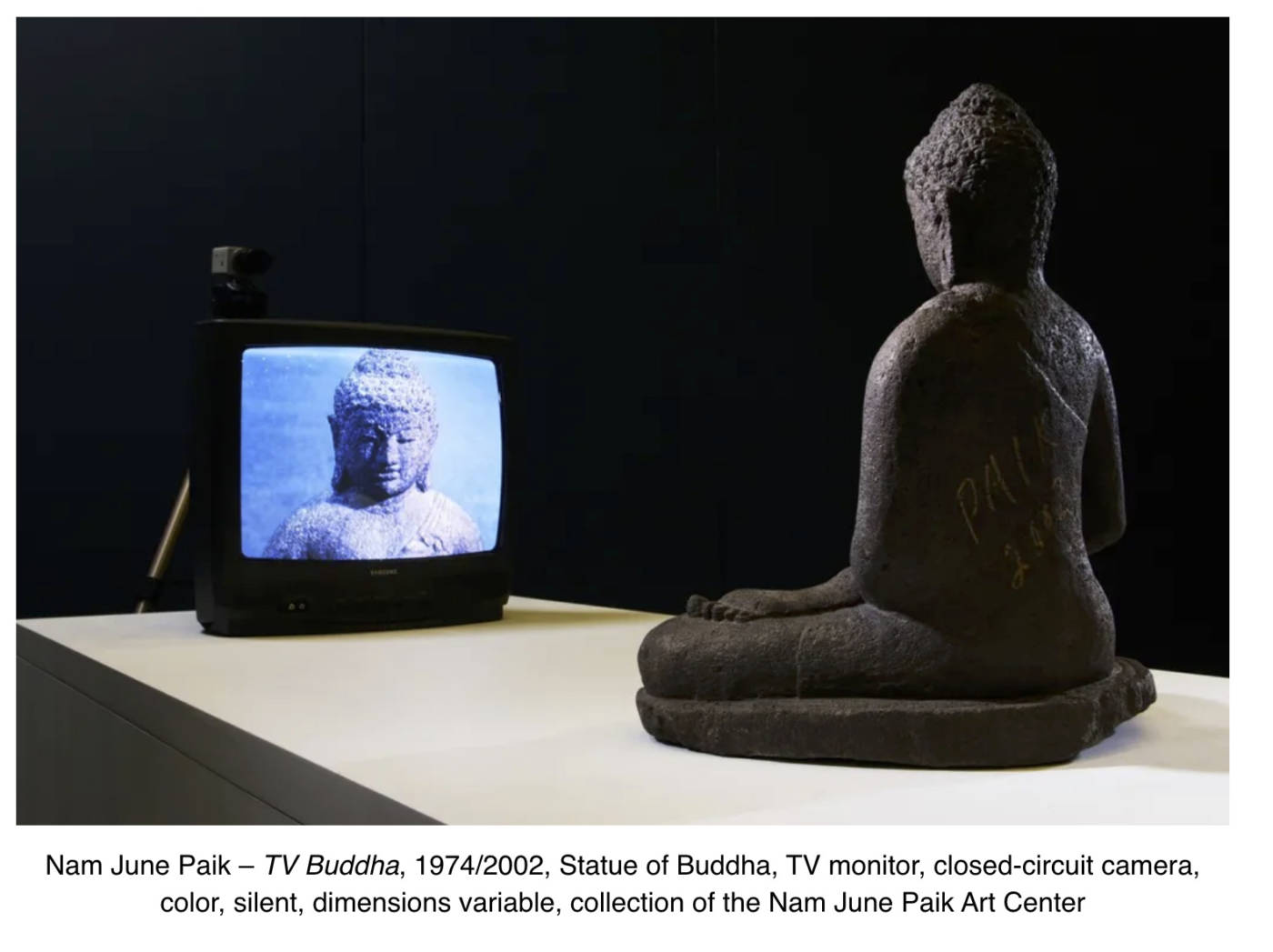

Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik was a Korean American artist, widely considered to be the founder of video art. From 1962 he was a member of the avant-garde art movement Fluxus, and was the first proponent of utilising television sets as the principal material component of his sculptural assemblies. He is credited with one of the first video works in the mid-Sixties after the introduction of hand held video recording equipment for the general population, making increasingly elaborate stacks of video monitors and television based sculptures from the 1970s onwards.

If conceptually informed artworks are ones in which an idea determines the work. You can think of some of the works below as a response to a simple, one sentence instruction. (From https://magazine.artland.com/history-of-video-art-part-i/)

Bruce Nauman

Born in 1941 in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Bruce Nauman has been recognized since the early 1970s as one of the most innovative and provocative of America’s contemporary artists. Nauman finds inspiration in the activities, speech, and materials of everyday life. Confronted with the question “What to do?” in his studio soon after leaving school, Nauman had the simple but profound realization that “If I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art. At this point art became more of an activity and less of a product.” (From https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s1/identity/)

William Wegman

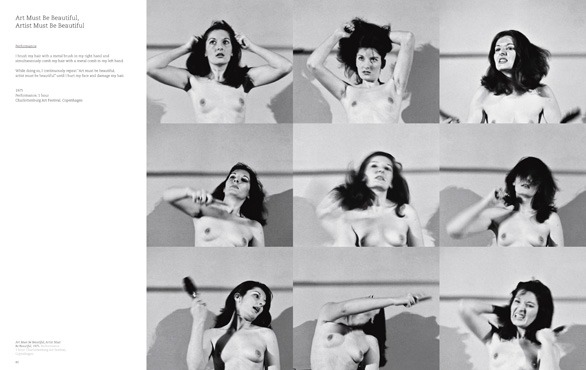

Marina Abramovic

Abramović was raised in Yugoslavia by parents who fought as Partisans in World War II and were later employed in the communist government of Josip Broz Tito. In 1965 she enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade to study painting. Eventually, however, she became interested in the possibilities of performance art, specifically the ability to use her body as a site of artistic and spiritual exploration. After completing postgraduate studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1972, Abramović conceived a series of visceral performance pieces that engaged her body as both subject and medium. In Rhythm 10 (1973), for instance, she methodically stabbed the spaces between her fingers with a knife, at times drawing blood. In Rhythm 0 (1974) she stood immobile in a room for six hours along with 72 objects, ranging from a rose to a loaded gun, that the audience was invited to use on her however they wished. These pieces provoked controversy not only for their perilousness but also for Abramović’s occasional nudity, which would become a regular element of her work thereafter.

Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful is one example of how, in the early years of performance art, female artists used their own bodies to challenge the institution of art and the notion of beauty. Marina has said in an interview that during the 1970s, “if the woman artist would apply make-up or put [on] nail polish, she would not have been considered serious enough.”

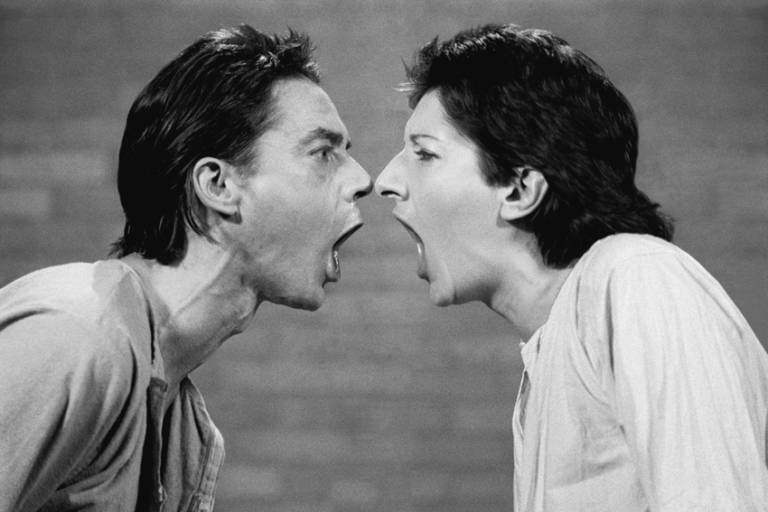

Breathing In/Breathing Out:

‘We are kneeling face to face, pressing our mouths together. Our noses are blocked with cigarette filters. I am breathing in oxygen. I am breathing out carbon dioxide.’

In their performance piece Breathing In/Breathing Out Marina Abramovic and Ulay blocked their noses with cigarette filters and clamped their mouths tightly together, breathing in and out each other’s air. After seventeen minutes they both fell to the floor unconscious. The viewers could sense the tension through the sound of their breathing, which was augmented through microphones attached to their chests. Is it a beautiful romantic gesture or a comment on how relationships absorb and destroy an individual?

“Something tender and violent at the same time emerges from the performance: the couple are decided to stick together despite the effort, the danger, the damage; but as is the case with human relations of this kind of intensity, they end up with violence, pain, and a part of each other ‘dead’. It is the idea of interdependency portrayed to its extreme.” Interartive

AAA-AAA (performance RTB, Liege), 1977

AAA-AAA centres on the relationship between two lovers. They started from an equal position to end up outdoing each other.

Abramovic, Marina; Ulay, «Rest Energy», 1980

Standing across from one another in slated position. Looking each other in the eye. I hold a bow and Ulay holds the string with the arrow pointing directly to my heart. Microphones attached to both hearts recording the increasing number of heart beats.

Rineke Dijkstra

Candice Breitz

Candice Breitz

‘Legend (A Portrait of Bob Marley),’ 2005

Breitz’s experiments in the field of portraiture can cumulatively be described as an ongoing anthropology of the fan.

In each case, Breitz first sets out to identify ardent fans of the musical icon to be portrayed, by placing ads in newspapers, magazines and fanzines, as well as on the Internet. Those who respond to this initial call (typically numbering in their hundreds) are then put through a rigorous set of procedures designed to exclude less than authentic fans of the celebrity in question, in order to arrive at the final group of participants.

The individuals who appear in these works have thus stepped forward to identify themselves as fans, and have been included purely on this basis: all other factors – their appearance; their ability to sing, act or dance; their gender and age – are treated as irrelevant for the purpose of selection. Each of the selected fans is offered the opportunity to re-perform a complete album, from the first song to the last, in a professional recording studio. The portraits evoke their mainstream entertainment counterparts (such as American Idol or Pop Idol), but also take significant distance from their reality television cousins: Breitz promises her subjects neither fame nor fortune. What she offers them is an opportunity to record the songs that have come to soundtrack their lives in whatever way they choose. The non-hierarchical grids that she uses to organize the final presentation of the fans in each portrait, allow Breitz to deliberately sidestep the question of who has fared better or worse under the conditions that she has created for these quasi-anthropological visual essays on the culture of the fan. Whether the fans who pay tribute to their icons in her portraits are victims of a coercive culture industry or users of a culture that they creatively absorb and translate according to their needs, is left to the viewer to decide. If the dignity of the portrayed fans remains surprisingly intact, it is because rather than prompting us to laugh at the fans that she lines up, Breitz forces us to reflect on the extent to which pop music has infiltrated our own biographies.

Titling the series of works as she does, Breitz asks that we locate these multi-channel installations within the genre of portraiture, and prompts the question of how they in fact relate to this most humanist of genres. (From the artist’s video channel)

Divya Mehra

Selections from Ryan Trecartin

Ryan Trecartin (b.1981) is a contemporary American artist who works largely in video. While his work often incorporates ideas and images related to social media and technology, he claims that he is interested primarily in relationships and the ways in which the Internet has changed how people relate to the world and one another.[1] While Trecartin often posts his movies online and draws recurring themes and motifs from Internet culture, he also builds sculptural environments and installations in museums for showing his work.[2] In What’s the Love Making Babies For, Trecartin employs digital manipulations, extreme editing, and chaotic dialogue in a way that is characteristic of his artistic style, creating a world that is “hyper-saturated with media.” [3] More relevant to the concerns of this program, he also engages with ideas of authority, expertise, and the dissemination of information, as his characters forward their often warped and sometimes indecipherable ideas surrounding “reproduction, sexuality, and contemporary moralities” by engaging with traditional formats such as the TV commercial.[4] However, Trecartin roots his movie in the digitized Internet landscape, thus evoking questions surrounding how modes of communication and information transmission transform and morph in the digital age. (From [1] Calvin Tomkins, “Experimental People,” The New Yorker, March 14, 2014, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/201…. [2] Ibid. [3] “What’s the Love Making Babies For,” Electronic Arts Intermix, accessed December 14, 2015, http://eai.org/title.htm?id=12291.he